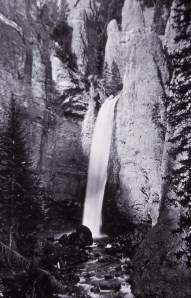

In 1909 travel writer F. Dumont Smith published this account of his hike to the base of the Lower Yellowstone Fall. Smith went down the canyon with two friends, Dudgeon and a man he called “the Banker.” Apparently, there were no stairs there at the time.

∞§∞

We found the little path that descends to the bottom of the gorge, tied our horses, and started down. At the brink there was a sign that remarked, in the most casual way, “Danger.” Dudgeon and I had a discussion as to whether it meant bears or female tourists, Dudgeon holding to the latter view. In the meanwhile, the Banker had plunged down and we followed.

If I had been in the lead, I should have abandoned the expedition right there; but Dudgeon and the Banker had gone and I was ashamed not to follow. At the bottom of the cleft there was a sheer descent.

At the bottom, we found a long ridge, fifty feet above the water that envisaged the fall. For myself, I was content to rest there while Dudgeon and the Banker pursued a path of slippery granite to the bottom of the gorge, where the water ran blue and white, full of foam from its mad descent above. While it frothed and fumed and made much of itself, it was not alarming for the Yellowstone seems but a shallow brook there, between those vast walls, dwarfed by the fall and the great canyon.

From the very bottom springs one great wonderful rainbow, a perfect arch, as steadfast as though it were of steel, one foot resting on the whirlpool and the other on the rock at the right. And two hundred feet above, where one little spurt of spray strikes a jut of stone, is a baby rainbow that comes and goes.

Above me loomed that awful chasm that must be climbed. It hung over me—settled on my spirits. I tried to smile; to admire the falls; I tried to enjoy that wonderful gorge, with its coloring, its beauty, its charm. I watched an eagle leave his eyrie on the very edge of the canyon and soar above me, wings atilt, without movement, and I led my companions into a discussion of flying machines and the problem of aviation. I drew their attention to a place on the rocks opposite, where the continuous spray had mottled its somber brown with a living green of moss.

I did everything that would hold their attention and postpone the hour when I must start back. At last, every subject exhausted, the Banker suddenly started upward. From our little cliff that overhung the maelstrom, the path led up a bare rock. When I looked at it in cold blood, I wondered how I ever descended it without wings. I knew in my heart that I could never get back, but the Banker started.

It was a sheer cliff, with here and there a crack, a toe-hold, or finger-hold as far apart as one could reach. I saw him toilsomely reach from one to the other, spread-eagled against the rock face. At one place, a rock, that he grasped with his right hand, as he threw his weight on it, gave way, glanced over his arm, and just missed his head. He swung far outward and I shuddered. I thought he was gone, and his body a mangled mass on the rocks a hundred feet below. By a miracle, his left hand held, and he still pursued his way, inch by inch.

I said to Dudgeon, “I never can make that, but you must stay below and catch me if I slip.” And Dudgeon smiled.

Like most men, I am a coward when there is no one around. Here were no admiring crowds to see me risk my life. No one but Dudgeon. How I scaled that awful cliff, I shall never know. I think I was years doing it. I hung there, sometimes by two fingers of each hand, my toes inserted into some tiny crack, panting for breath, benumbed, speechless, sweating at every pore. Sometimes it seemed hours before I could move.

I was safe enough as long as I stood still. My body in my anguish put out spores and tentacles that grasped the rock. I was for a time a limpet, one of those intermediate forms of life that cling and cling and never move.

It was when I tried to progress that the strain became too great. The Banker had vanished. Dudgeon was somewhere far above me whistling “My Bonnie,” and there I clung, a mere gastropod. I doubt if, in those awful moments, I had any more intelligence than a vegetable. All I felt was fear—fear of those spear-like rocks down there below me.

What a curious thing pride is! If I had been alone with Dudgeon I should have called for rope and tackle and a hoisting engine. But the Banker had passed before me, and so, however Dudgeon smiled, I could not quit.

I knew that, at the very top, awaited me that terrible rocky slide, almost perpendicular and slimed with past ages of moisture. When I thought of that I was ready to die, but when I had attained it, there, hanging from the top of the path, was a rope.

Somehow I grasped that rope. Somehow I scrambled up that rocky slide by its aid and sank half fainting at the top. There was not air enough in the universe to satisfy me. The wide scope of the heavens, of the starry skies, did not contain enough atmosphere to fill my starved and laboring lungs.

Slowly and painfully the Banker and I climbed the rest of the hill. Slowly and painfully we got into our surrey. Meanwhile Dudgeon had danced and jigged his way up those slopes, whistling “My Bonnie,” and, when we finally seated ourselves in the surrey, he was as unbreathed as though he had just finished a two-step.

If you go down the corridor of the Canyon Hotel, and turn to the right, at the second door you can find something in a glass with ice in it; and there once more Dudgeon smiled.

∞§∞

— Abridged from F. Dumont Smith, The Summit of the World: A Trip Through Yellowstone Park, 1909.

— Photo, Yellowstone Digital Slide File.

— You might enjoy Louis Downing’s story about going to the base of the Fall down Uncle Tom’s Trail.

Just as important the as credibility of members of the Washburn Expedition was their writing skill. Several expedition members wrote articles about the trip for the Helena Herald that were reprinted around the world.

Just as important the as credibility of members of the Washburn Expedition was their writing skill. Several expedition members wrote articles about the trip for the Helena Herald that were reprinted around the world.  Here and there are small groves, and the timber is quite thick a mile away from the river. A quarter of a mile above the upper falls the river breaks into rapids, and foams in eddies about huge, granite boulders, some of which have trees and shrubs growing upon them.

Here and there are small groves, and the timber is quite thick a mile away from the river. A quarter of a mile above the upper falls the river breaks into rapids, and foams in eddies about huge, granite boulders, some of which have trees and shrubs growing upon them.