Not all stories about Yellowstone Park are high adventures like battling Indians, or tumbling down canyons, or falling in geysers. Some are just sweet little tales about young people falling in love. Here’s an example.

∞§∞

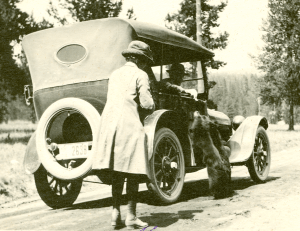

The giant Speedex hummed out of Bozeman with its load of khaki-clad, riding-trousered women and men in old army uniforms. The running-board was piled high with the dunnage which accompanies an automobile tour, and in back, two burly, grey, spare tires rode majestic. The giant Speedex was bound for the Yellowstone Park.

Not two minutes behind roared Winsted Tripp’s fiery roadster. The girl was in the big machine ahead. In the hotel the night before, Win had noted the entrance of the party; had heard the clerk describing the route they must take to get to the Park and had observed the girl. So it was that he had arisen early, and was now sailing along with the top down and windshield up, the breeze blowing over his thick hair and over the iron-grey ambrosial locks of old Pop Slocum, who was accompanying him on his trip through the Park.

All morning long the roadster sped down the Yellowstone Trail on its way to the Gardiner gateway. Win kept a lookout for the Speedex, and twice sighted the big spare tires down the dustless road ahead. He aimed to travel a short distance behind the other party, and if necessary assist Fate in decreeing that they should stop at the same hotel that night.

They made Mammoth Hot Springs about half-past four and secured a room. Then the young man with his old comrade went for a tour of the great hot springs formation. It was the cool of the afternoon, and the white limestone dust on the formation looked like snow. Old maids, college professors, geologists, guides, bored tourists, were everywhere, giving the multitudinous colored pools, spiderweb limestone deposits, and other wonders the great American “once-over.”

Win thought once that he glimpsed the girl, but he couldn’t be sure.

Those nights at Mammoth Hotel! The stars sparkling in the dry air of that high altitude; the arc lights flaring like giant diamonds around the grounds; the dance-floor in the hotel swimming in color as the couples sway to the orchestra’s jangling tunes; the scent of balsam firs that pervades everything in the Park . . . Nights of romance!

“Go in and dance,” urged Pop Slocum. “You may not know yon gay damsels, but tell ’em you’re a gentleman and are taking as much risk as they are anyhow, and I’ll bet no one will object.”

But Win preferred to sit on the sidelines and watch the dancers. He had been a male wallflower since the first dance he had ever attended. He couldn’t talk to girls, that was the trouble; he always felt called on to say something humorous or brilliant, and always managed to stammer out some peculiarly stupid remark.

And so, melancholy came upon Win, and he began to be afraid of his interest in the girl. She was too far above him, he concluded; she’d never understand. Finally, he went upstairs to bed.

The travellers went on early the next morning. They were getting into the heart of the great reserve, and the roads were becoming ever more tortuous and steep, though their ribbon-smooth surfacing continued.

Pop Slocum was surprised by Win’s gloomy silence in the seat beside him. The old man had turned and stared for perhaps thirty seconds, while Win tried to look unconscious of it but felt the hot blood climbing to his ears.

“My God!” finally boomed the old man. “I might have known as much!”

“Known what?” asked Win.

“You’re in love, my boy, in love! That’s my diagnosis!”

Win grinned like a twelve-year-old boy.

“Correct you are, Pop,” he admitted.

###

The Norris Geyser Basin rushed upon them around a curve, and Win drove his car off to the side of the road and stopped with a squall of brake linings. Below them was spread the basin, like the roof of hell’s kitchen, smoking and steaming and hissing in a thousand vents.

The two men set out for the basin They had walked hardly a dozen steps when the old man grasped Win’s arm.

“There she is, lad!” he whispered, pointing towards the party out on the walk.

And there indeed she was, clad in an abbreviated yellow coat, khaki breeches, puttees, and battered old army hat. Win quickened his pace, and the old man giggled excitedly.

“Now, leave it to me, Bud,” he instructed. “Just follow my lead, and keep wide awake.”

They approached the party with all decent speed; the others had paused to examine a steam vent, and in no time, Win was able to get a satisfactory glance at the group. Pop Slocum was not idle. He had a way with him which never gave offense, yet admitted him to any company on terms of friendly and jovial intimacy. He had introduced himself and Win all around within three minutes.

And the girl? She smiled at Win frankly, as if she were meeting a friend again. She was about to say something, when Pop suddenly slipped and nearly tumbled into the hot water that lay on the thin crust of the basin. He grasped frantically and in so doing kicked the girl’s foot so as to shove her towards Win.

She lost her balance, and fell into Win’s arms. Perhaps he held her longer than was really necessary; at any rate he saw that she was thoroughly steady and in no danger of falling before letting her go. Pop had recovered, and the incident passed off. But Dorothy Brown’s cheeks were bright with color; and Winsted Tripp was reduced to embarrassed silence.

###

It was evening at the Grand Canyon Hotel. In the lobby the jazz band was putting “pep” into the couples weaving in and out on the polished floor. On the porch the older men smoked and talked of war and bolshevism and stockmarkets and automobiles, while the women gathered in those familiar gossip-circles which they can never forego, although they have the vote, and sit in Congress.

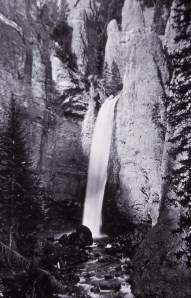

A steep winding trail leads down from the Canyon hotel to a platform overlooking the lower falls of the Yellowstone. Here Win had come, to sit in the moonlight and bid farewell to the romance he had possessed

The night was bright with a full moon, and the canyon of the Yellowstone stretched away before him into infinity, a grey giant, dreaming under the stars. The roar of the river had become nearly soundless to Win’s ears, its steady noise turning his nerves to its own pitch.

He was aroused from his reflections by the presence of someone else on the platform. He looked again, and rubbed his eyes.

“Oh, so it’s you back again,” he said confusedly.

“Yes,” said Dorothy Brown, “It’s I, back again.”

Her tone had a little gladness that Win could not mistake. In that moment he knew his heart had found its objective

∞§∞

— Condensed from R. Maury, “A Yellowstone Rencontrem,” The University of Virginia Magazine, October 1919, pp. 221-232.

— “Bear on the Running Board,” Pioneer Museum of Bozeman Photo.

— “Ballroom Scene,” detail from Library of Congress Photo.

General George W. Wingate, a wealthy New Yorker, took his wife and 17-year-old daughter to Yellowstone Park in 1885. Although there were roads by then, the Wingates decided to travel on horseback and the women rode sidesaddle. Here’s General Wingate’s description of an incident that occurred while the ladies were riding through the Paradise Valley north of Yellowstone Park.

General George W. Wingate, a wealthy New Yorker, took his wife and 17-year-old daughter to Yellowstone Park in 1885. Although there were roads by then, the Wingates decided to travel on horseback and the women rode sidesaddle. Here’s General Wingate’s description of an incident that occurred while the ladies were riding through the Paradise Valley north of Yellowstone Park.