In the summer of 1877, several bands of Nez Perce abandoned their homeland in Idaho and eastern Oregon in hopes of making a new life in the buffalo country of Montana. Pursued by the Army, they fled through Yellowstone Park.

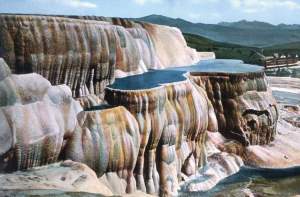

Although the Nez Perce chiefs wanted to avoid contact with whites, a group of young men separated from the main Indian body and attacked several groups of tourists. On August 26, the Indians attacked a group from Helena, Montana, killing one of them and forcing others flee. Most of the survivors made their way to the incipient resort at Mammoth Hot Springs.

After waiting for two days for stragglers to come in, the leader of the Helena tourists, Andrew Weikert, got the owner of the resort, James McCartney, to return with him to the scene of the attack. They planned to look for two men who hadn’t returned and bury one they knew had been killed. Here’s Weikert’s story of their adventure.

∞§∞

While McCartney and I were on our way from the Springs to the old camp, this same band of Indians passed us somewhere, but we did not see them at that time. We went within two miles of the old camp and unpacked and stayed all night, for it was too late to go farther.

We started early the next morning and got into the old camp, then began our search. We soon found Kenck’s body and buried it the best we could. We found his watch in his pocket and ring on his finger, which the Indians had missed. We spent the remainder of the day searching for the other two missing boys, but not finding them, concluded that they had made their escape.

We packed up what little was left in the camp and started back, camping at night where we did the night before; had our supper then made down our bed, then went to picket our horses so they could not go too far away.

Mack said, “Andy, something tells me we had better go on.” I told him all right, so we saddled up and started. I looked back through an opening in the timber and saw an Indian ride across, so we “lit out” pretty lively for a little ways. I presume he wanted to find out how we were fixed, but we slipped them that time and traveled on until 3 o’clock in the morning, then crossed the Yellowstone and camped until morning.

It was about 9 o’clock when we found our horses, for we had to turn them loose so that they could get something to eat. Had almost come to the conclusion that the Indians had stolen them. We, at this time, were about eighteen miles from the Springs. We saddled and packed our horses then started to the Springs.

We met a party of Indians on the trail; got within two hundred yards of them before we saw them. There were eighteen of them, so we thought there was not much chance for us. So we struck out for the nearest brush.

We had a lively race for a mile, for the Indians were firing at us all the time and trying to head us off from the brush. Eighteen guns kept up quite a racket and they got some of the balls in pretty close. We could hear the balls whistle through the air and see them pick up the dust.

We returned fire as best we could and think we made some good Indians. We rode together for some time, then Mack started right straight up the hill for the brush. I kept out on the hillside more so as to give my horse a better chance.

The Indians got off their horses and kept right behind a reef of rocks, so we had rather a poor chance to return fire, but they kept pouring the lead into the hill close around me all the time, for they were not over two hundred yards from me. But they soon put a ball into my horse and he stopped as quick as a person could snap his finger. I knew that something was wrong, so I got off quick and in an instant saw the blood running out of his side.

So I said, “Goodbye Toby, I have not time to stay, but must make the rest of the way afoot.” I made all speed possible for the brush, for I could not see enough of the Indians behind the rocks to shoot at and had no cartridges to waste. We had fired several shots apiece.

About this time, Mack’s horse commenced bucking (the saddle had got back on his rump,) and bucked him off, then ran out to where I was, and followed up after me with the saddle under him. I took my knife after me, from my belt and was going to try and catch him, if he would come close enough, then cut the saddle loose and jump on him, but he tramped on the saddle and away he went.

The Indians never let up shooting, but kept picking up the dust all around me. I think they must have fired fifty shots at me, but only cut a piece out of my boot leg and killed my horse. He had keeled over before Mack and I got together.

Mack wanted to get down behind a big log that was lying close by, but I looked up and saw the reds almost over our heads, I then told him that I was going for the brush. He asked me to wait until he would take off his spurs, then he would go with me. He put his hand on my shoulder and yanked off his spurs, throwing them down towards the log saying they might lie there until some time later he might call for them.

While he was taking off his spurs the reds fired three shots at us. I don’t think either of them was over ten feet from us. I made the remark that they were coming pretty thick; Mack says “Just so.”

We soon got to the brush, but there was no reds to be seen anywhere. They were terrible brave so long is they had the advantage, but just as soon as the tables were turned, they made themselves scarce behind the hills, as they will not follow a man into the brush.

We camped there for about an hour, then ventured out to see if the walking was good, or probably they had missed one of our horses. We did not find any except the dead, and from even this they had taken my saddle and bridle. We saw the Indians about four miles off so concluded to make it on foot to the Springs.

∞§∞

Weikert later returned to retrieve the dead man’s body and take it to Helena for a proper burial. Soldiers pursuing the Nez Perce rescued the two missing men.

I’m working on a book titled Encounters in Yellowstone 1877 that will chronicle more stories of Yellowstone tourists who ran afoul of the Indians.

∞§∞

Adapted from Weikert’s Journal published in Contributions to the Montana Historical Society, 1900.

— NPS photo from the Yellowstone Digital Slide File.

— You might enjoy:

- Andrew Weikert’s description of another gun battle with the Nez Perce.

- Emma Cowan’s tale of being taken captive.

For other related stories, click “Nez Perce” under the categories button.