Thomas Moran began conjuring images of the upper Yellowstone before he even saw the place. Moran was an illustrator for Scribner’s Monthly and provided drawings for N.P. Langford’s article about the famous Washburn expedition of 1870.

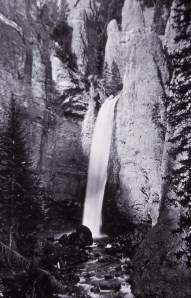

While learning to paint, Moran sought inspiration from literary works such as Longfellow’s “Hiawatha,” so it wasn’t hard for him to base his illustrations entirely on Langford’s words. The results were interesting (if sometimes inaccurate). Below is what Langford said about Tower Fall and how Moran pictured it.

∞§∞

Tower Creek is a mountain torrent flowing through a gorge about forty yards wide. Just below our camp, it falls perpendicularly over an even ledge 112 feet, forming one of the most beautiful cataracts in the world. For some distance above the fall, the stream is broken into a great number of channels each of which has worked a torturous course through a compact body of shale to the verge of the precipice where they re-united and form the fall.

The countless shapes into which the shale has been wrought by the action of the angry waters, add a feature of great interest to the scene. Spires of solid shale, capped with slate, beautifully rounded and polished, faultless in symmetry, raise their tapering forms to the height of from 80 to 150 feet, all over the plateau above the cataract. Some resemble towers, others spires of churches, and others still shoot up as lithe and slender as the minarets of a mosque.

Some of the loftiest of these formations, standing like sentinels upon the very brink of the fall, are accessible to an expert and adventurous climber. The position attain on one of their narrow summits, amid the uproar at a height of 250 feet above the boiling chasm, as the writer can affirm, requires a steady hand and strong nerves; yet the view which rewards the temerity of the exploit is full of compensations.

Below the fall the stream descends in numerous rapids, with frightful velocity, through a gloomy gorge, to its unions with the Yellowstone. Its bed is filled with enormous boulders, against which the rushing waters break with great fury. Many of the capricious formations wrought from the shale excite merriment as well as wonder. Of this kind especially was a huge mass sixty feet in height, which, from its supposed resemblance to the proverbial foot of his Satanic Majesty, we called the ‘Devil’s Hoof.’

The scenery of mountain, rock, and forest surrounding the falls is very beautiful. Here too, the hunter and fisherman can indulge their tastes with the certainty of ample reward. As a halfway resort to the greater wonders still farther up the marvelous river, the visitor of future years will find no more delightful resting place. No account of this beautiful fall has ever been given by any of the former visitors to this region. The name of “Tower Falls,” which we gave it, was suggested by some of the most conspicuous features of the scenery.”

∞§∞

Moran actually got to see Tower Fall in 1871 when he accompanied the government explorer, F.V. Hayden there. During the two days Moran spent at Tower Fall, he must have worked diligently making sketches from various vantage points in ink and watercolor. He used these en plain air studies later to produce several paintings in his studio.

A year after the Washburn Expedition, Moran produced the full color rendition seen below. This piece reflects the Romantic Hudson River School that dominated American art at the time. It is characterized by aerial perspective, concealed brushstrokes and luminist techniques that made the landscapes seem to glow.

In 1875, Moran offered the version of Tower Fall shown at the top of this post that is more impressionistic in that it juxtaposes elements in ways that can’t be seen from any actual viewpoint. Moran, who famously said, “I place no value upon literal transcripts from Nature,” was a Romantic who sought to reproduce the emotional rapture that some landscapes evoke.

∞§∞

— The magazine illustration and N. P. Langford’s description are from his article “The Wonders of the Yellowstone.” Scribner’s Monthly, 2(1) 1-16 (May, 1871)

— Other images are from the Coppermine Gallery.

— For more on Moran’s Legacy, click on “Thamas Moran” under the Categories button to the left.

— You might also enjoy N.P. Langford’s humorous tale about the naming of Tower Fall.