For decades trappers and prospectors told about the wonders in the upper Yellowstone, but their reports usually were dismissed as tall tales and few people visited the remote area. But interest soared within a year of the Washburn Expedition’s return after their exploration in 1870.

Soon the race was on for tourists dollars with Bozeman businessmen building a road up Yankee Jim Canyon on the north and their Virginia City counterparts doing the same over Targhee Pass on the west. Tourists began arriving before the roads were done. Also, entrepreneurs were building hotels and bathhouses and planning stagecoach service.

The reason the Washburn Expedition generated interest while earlier groups had failed was that it included prominent men whose word couldn’t be doubted—and several of them were skilled writers who published their reports immediately in Montana newspapers. One of these writers, was Henry Washburn himself. He was a distinguished Civil War officer and Surveyor General of Montana Territory. Here’s an excerpt describing the Great Falls of the Yellowstone from the report Washburn wrote for the Helena Daily Herald just days after getting home.

∞§∞

The party crossed over a high range of mountains and in two days reached the Great Falls. In crossing the range, from an elevated peak a very fine view was had. The country before us was a vast basin. Far away in the distance, but plainly seen, was the Yellowstone Lake: around the basin the jagged peaks of the Wind River, Big Horn, and Lower Yellowstone ranges of mountains; while just ever the lake could be seen the tops of the Tetons.

Our course lay over the mountains and through dense timber. Camping for the night eight or ten miles from the falls, we visited some hot springs that, in any other country, would be a great curiosity, boiling up two or three feet, giving off immense volumes of steam, while their sides were incrusted with sulphur. It needed but a little stretch of imagination on the part of one of the party to christen them “Hellbroth Springs.”

Our next camp was near the Great Falls, upon a small stream running into the main river between the upper and lower falls. This stream has torn its way through a mountain range, making a fearful chasm through lava rock, leaving it in every conceivable shape. This gorge was christened the’” Devil’s Den.” Below this is a beautiful cascade, the first fall of which is 5 feet, the second 20 feet. and the final leap 84 feet. From its exceedingly clear and sparkling beauty it was named “Crystal Cascade.”

Crossing above the upper falls of the Yellowstone, you find the river one hundred yards in width, flowing peacefully and quiet. A little lower down it becomes a frightful torrent, pouring through a narrow gorge over loose boulders and fixed rocks, leaping from ledge to ledge, until, narrowed by the mountains and confined to a space of about 80 feet, it takes a sudden leap, breaking into white spray in its descent, 115 feet.

Two hundred yards below, the river again resumes its peaceful career. The pool below the falls is a beautiful green, capped with white. On the right-hand side a clump of pines grows just above the falls, and the grand amphitheater, worn by the maddened waters on the same side, is covered with a dense growth of the same.

The left side is steep and craggy. Towering above the falls, half-way down and upon a level with the water, is a projecting crag, from which the falls can be seen in all their glory. No perceptible change can be seen in the volume of water here from what it was where we first struck the river. At the head of the rapids arc four apparently enormous boulders, standing as sentinels in the middle of the stream. Pines are growing upon two of them. From the upper fall to the lower there is no difficulty in reaching the bottom of the canyon.

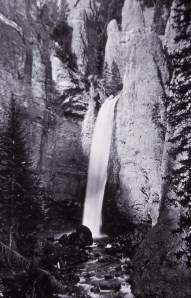

The lower falls are about half a mile below the upper. where the mountains again, as if striving for the mastery, close in on either side, and are not more than 70 feet apart. And here the waters are thrown over a perpendicular fall of 350 feet.

The canyon below is steep and rocky, and volcanic in its formation. The water, just before it breaks into spray, has a beautiful green tint, as has also the water in the canyon below. Just below, on the left-hand side, is a ledge of rock, from which the falls and the canyon may be seen. The mingling of green water and white spray with the rainbow tints is beautiful beyond description.

The canyon is a fearful chasm, at the lower falls a thousand feet deep, and growing deeper as it passes on, until nearly double that depth. Jutting over the canyon is a rock 200 feet high, on the top of which is an eagle’s nest, which covers the whole top. Messrs. Hauser, Stickney, and Lieutenant Doane succeeded in reaching the bottom, but it was a dangerous journey. Two and a half miles below the falls, on the right, a little rivulet, as if to show its temerity, dashes from the top of the canyon, and is broken into a million fragments in its daring attempt.

∞§∞

— From Henry Washburn, “The Yellowstone Expedition,” Helena Daily Herald, September 27 and 28, 1870.

— Frank J. Haynes postcard, Yellowstone Digital Slide File.

— You might also enjoy General Washburn’s description of geysers.

— For more stories about the Washburn Expedition, click on “Washburn” under the “Categories” button to the left.