The big event on my schedule this week is my presentation, “The Nez Perce in Yellowstone,” to Smart Women on Wednesday at 3 p.m. at Aspen Point, an assisted living facility in Bozeman. I’m still working on my slides and script, but it’s taking shape in my mind.

I’ll begin with an overview of the flight of the Nez Perce who generally lived peacefully with whites for most of the 1800’s. After gold was discovered on Nez Perce land in 1853, settlers began moving in and in 1877 the Indians were ordered onto a tiny reservation. Rather than comply with the order, they decided to flee to the buffalo country on the plains. Most accounts of the flight of the Nez Perce emphasize things that happened outside of Yellowstone Park like broken treaties and battles, but I’ll reverse that pattern and focus in the human drama of the Indians’ encounters with tourists.

Then I’ll talk about what I call “The Joseph Myth,” the common belief that Chief Joseph was a great general whose genius allowed him to outmaneuver the U.S. Army for months. Joseph was the chief of one of the five bands that led the army on its merry chase, but he was never the principal chief. I’ll speculate on reasons the Joseph Myth was born and why it persistes: (1) Joseph was an important chief who had a conspicuous role in negotiations with whites before the Nez Perce decided to leave and he was the last remaining chief at the Battle of Beartooth so he negotiated the surrender. These things made him the apparent leader. (2) The Army Officers needed a genius opponent, otherwise they would look like fools for letting a band of Indians that included old men, women and children—and 1,600 hundred horses and cow—elude them for months, (3)After the conflict Indian sympathizers needed an Indian hero who sought peace to bolster their case, and (4) Joseph was indeed a noble man who devoted his life to obtaining justice for his people. All true, but he wasn’t a military genius.

I’ll talk about the Radersburg Party’s trip to the park and read Emma Cowan’s description of her being taken captive by the Nez Perce, which ended with her watching an Indian shoot her husband in the head.

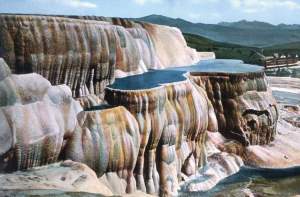

To slow things down, I’ll talk about “Skedaddlers,” tourists who visited the park in the summer of 1877, but left before the Indians arrived. These include: the famous Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman; Bozeman Businessman Nelson Story; English Nobleman and park popularizer, The Earl of Dunraven and his companions, Buffalo Bill’s sometime partner, Texas Jack Omohundro, and Dunraven’s friend, George Henry Kingsley, a physician who patched up the Nez Perce’ victims at Mammoth Hot Springs.

I’ll talk about the Helena Party’s trip and contrast the all-male group that entered the park from the north with the co-ed Radersburg Party that entered from the west. Then I’ll read Andrew Weikert’s description of his gun battle with the Nez Perce.

Then I’ll describe how survivors of encounters with the Nez Perce were either rescued by soldiers looking for the Indians or made their way to Mammoth Hot Springs. I’ll explain that after Emma Cowan, her sister, and several wounded men left Mammoth for civilization, three men stayed there to see if their missing companions would appear. Then I’ll read Ben Stone’s description of the Indian attack at Mammoth that left another man dead.

I’ll end with my synthesis of accounts of Emma Cowan’s overnight ride from Helena to Bottler’s Ranch in the Paradise Valley to join her husband who had survived three gunshot wounds and was rescued by the army. That will give me an opportunity to talk about Encounters in Yellowstone, a book I’m writing now.

∞§∞

— The presentation is free and open to the public. Please tell your friends.

— You can read about my 2011 presentation to Smart Women.

— Public Domain Photo.