During the summer of 1877, William Tecumseh Sherman, who was then commanding general of the U.S. Army, decided to tour the forts along the proposed route of the Northern Pacific Railroad. That was just one year after a coalition of Sioux and Cheyenne decimated the Seventh Cavalary under George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. In fact, the army was still patrolling the northern plains after the Sioux Chief Sitting Bull fled toi Canada. In addition, several bands of Nez Perce refused to move to a reservation in Washington and were headed to Montana.

Like many military officers, Sherman was fascinated with Yellowstone Park and had read several army and civilian reports about it. He knew about the Nez Perce troubles, but he decided to take a side trip to see the wonders of Yellowstone Park anyway. He was convinced that the Indians would not enter the park because they feared the geothermal features so he traveled with a small party of about a dozen men. After a 15-day tour, Sherman and his companions returned to Fort Ellis, near Bozeman, Montana, just a few days before the Nez Perce entered the park.

Here’s an abridged version of Sherman’s report of his trip to Yellowstone Park.

∞§∞

I suppose you want to hear something of the National Park, or “Wonderland,” as it is called here. As you know, I came from the Big Horn here with two light spring-wagons and one light wagon, with six saddle horses. Here we organized the party: Colonels Poe, Bacon, my son and self, three drivers, one packer, four soldiers, and five pack mules; making four officers, four soldiers, one citizen, and twenty-three animals. The packer was also guide.

Our rate of travel was about 20 miles a day or less. Our first day’s travel took us southeast over the mountain range to the valley of the Yellowstone; the next two days up the valley of the Yellowstone to the mouth of Gardner’s River. Thus far we took our carriages, and along the valley found scattered ranchos, at a few of which were fields of potatoes, wheat, and oats, with cattle and horses.

At the mouth of Gardner’s River begins the park, and up to that point the road is comparatively easy and good, but here begins the real labor; nothing but a narrow trail, with mountains and ravines so sharp and steep that every prudent horseman will lead instead of ride his horse, and the actual labor is hard.

The next day is consumed in slowly toiling up Mount Washburn, the last thousand feet of ascent on foot. This is the summit so graphically described by Lord Dunraven in his most excellent book recently published under the title of the “Great Divide.” The view is simply sublime, worth the labor of reaching it once, but not twice. I do not propose to try it again.

Descending Mount Washburn, by a trail through woods, one emerges into the meadows or springs out of which Cascade Creek takes its water; and following it to near its mouth you camp, and walk to the Great Falls and the head of the Yellowstone Canyon. In grandeur, majesty, coloring, &c., these probably equal any on earth. The painting by Moran in the Capitol is good, but painting and words are unequal to the subject. They must be seen to be appreciated and felt.

The next day, eight miles up from the falls, we came to Sulphur Mountain, a bare, naked, repulsive hill, but of large extent, at the base of which were hot bubbling springs, with all the ground crisp with sulphur; and six miles farther up, or south, close to the Yellowstone, we reached and camped at Mud Springs.

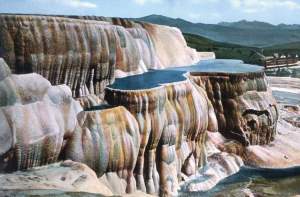

From the Mud Springs the trail leads due west, crosses the mountain range to the Lower Geyser Basin. It would require a volume to describe these geysers in detail. It must suffice now for me to say that the Lower Geyser Basin presents a series of hot springs or basins of water coming up from below, hot enough to scald your hand, boil a ham, egg, or anything else; clear as crystal, with basins of every conceivable shape, from the size of a quill to actual lakes a hundred. Yards across. In walking among and around them, one feels that in a moment he may break through and be lost in a species of hell.

Six miles higher up the West Madison is the Upper Geyser Basin—the “spouting geysers,” the real object and aim of our visit. To describe these in detail would surpass my ability, or the compass of a letter. They have been described by Lieutenant Doane, Hayden, Strong, Lord Dunraven, and many others. The map by Major Ludlow, of the Engineers, locates the several geysers accurately. We reached the Upper Geyser Basin at twelve noon, one day, and remained there till 4 p.m. of the next. During that time we saw the ” Old Faithful” perform at intervals varying from 62 minutes to 80 minutes.

Each eruption was similar, preceded by about live minutes of sputtering, and then would arise a column of hot water, steaming and smoking, to the height of 125 or 130 feet, the steam going a hundred or more feet higher, according to the state of the wind. It was difficult to say where the water ended and steam began; and this must be the reason why different observers have reported different results. The whole performance lasts about five minutes, when the column of water gradually sinks, and the spring resumes its normal state of rest.

This is but one of some twenty of the active geysers of this basin. For the time we remained we were lucky, for we saw the Beehive twice in eruption, the Riverside and Fan each once. The Castle and Grotto were repeatedly in agitation, though their jets did not rise more than 20 feet. We did not see the “Giant” or the ” Grand ” in eruption, but they seemed busy enough in bubbling and boiling.

In our return trip we again visited points of most interest and some new ones. The trip is a hard one and cannot be softened. The United States has reserved this park, but has spent not a dollar in its care or development. The paths are mere Indian trails, in some places as bad as bad can be. There is little game in the park now; we saw two bear, two elk, and about a dozen deer and antelope, but killed none. A few sage-chickens and abundance of fish completed all we got to supplement our bacon.

We saw no signs of Indians, and felt at no moment more sense of danger than we do here. Some four or five years ago parties swarmed to the park from curiosity, but now the travel is very slack. Two small parties of citizens were in the park with us, and on our return we met several others going in, but all were small.

∞§∞

— Abridged from Reports of the Inspection Made in the Summer of 1877 by Generals P.H. Sheridan and W.T. Sherman. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1878. (Pages 34-37)

— Photo from Wikipedia Commons.

— For related stories click “Nez Perce” under the Categories button.