Few of the Mountain Men who scoured the Rocky Mountains looking for beaver had the skill or inclination to write about their experiences. A conspicuous exception is Osborne Russell who trapped in Yellowstone Park in the late 1830’s.

He also described some thrilling adventures. Here’s one of them.

∞§∞

We encamped on the Yellowstone in the big plain below the lake. The next day we went to the lake and set our traps on a branch running into it near the outlet on the northeast side. After setting my traps I returned to the Camp.

The day being very warm, I took a bath in the lake for probably half an hour and returned to camp about 4 o’clock After eating a few minutes, I arose and kindled a fire, filled my tobacco pipe and sat down to smoke. My comrade whose name was White was still sleeping. Presently I cast my eyes towards the horses, which were feeding in the Valley and discovered the heads of some Indians gliding round within 30 steps of me.

I jumped to my rifle and aroused White while looking towards my powder horn and bullet pouch. They were already in the hands of an Indian and we were completely surrounded. We cocked our rifles and started through their ranks into the woods, which seemed to be completely filled with Blackfeet who rent the air with their horrid yells.

On presenting our rifles they opened a space about 20 feet wide through which we plunged. About the fourth jump an arrow struck White on the right hip joint. I hastily told him to pull it out. As I spoke another arrow struck me in the same place, but the arrows did not retard our progress. At length another arrow striking through my right leg above the knee benumbed the flesh so that I fell with my breast across a log. The Indian who shot me was within eight feet and made a spring towards me with his uplifted battle-axe. I made a leap and avoided the blow and kept hopping from log to log through a shower of arrows that flew around us like hail.

After we had passed them about ten paces we wheeled about and took aim at them. They then began to dodge behind the trees and shoot their guns. We then ran and hopped about fifty yards further in the logs and bushes and made a stand.

I was very faint from the loss of blood and we set down among the logs determined to kill the two foremost when they came up and then die like men. We rested our rifles across a log—White aiming at the foremost and myself at the second. I whispered to him that when they turned their eyes toward us to pull trigger.

About twenty of them passed by us within fifteen feet without casting a glance towards us another file came round on the opposite side within twenty or thirty paces closing with the first a few rods beyond us and all turning to the right. The next minute they were out of our sight among the bushes. They were all well armed with fusees, bows and battle-axes.

We sat still until the rustling among the bushes had died away then arose after looking carefully around us. White asked in a whisper how far it was to the lake. I replied by pointing to the southeast about a quarter of a mile. I was nearly fainting from the loss of blood and the want of water.

We hobbled along forty or fifty rods and I was obliged to sit down for a few minutes, then go a little further, and then rest again. We managed in this way until we reached the bank of the lake. Our next object was to obtain some of the water as the bank was very steep and high. White had been perfectly calm and deliberate, but now his conversation became wild hurried. Despairing, he observed, “I cannot go down to that water for I am wounded all over—I shall die.” I told him to sit down while I crawled down and brought some in my hat. This I effected with a great deal of difficulty.

We then hobbled along the border of the Lake for a mile and a half when it grew dark and we stopped. We could still hear the shouting of the savages over their booty. We stopped under a large pine near the lake and I told White I could go no further

“Oh” said he, “let us go up into the pines and find a spring,” I replied there was no spring within a mile of us, which I knew to be a fact.

“Well,” said he, “if you stop here I shall make a fire.”

“ Make as much as you please,” I replied angrily; “this is a poor time now to undertake to frighten me into measures.” I then started to the water crawling on my hands and one knee and returned in about an hour with some in my hat.

While I was at this he had kindled a small fire and taking a draught of water from the hat he exclaimed, “Oh dear we shall die here, we shall never get out of these mountains.”

“Well,” said I, “if you persist in thinking so you will die but I can crawl from this place upon my hands and one knee and kill two or three elk and make a shelter of the skins, dry the meat until we get able to travel.” In this manner I persuaded him that we were not in half so bad a situation as we might be although he was not in half so bad a situation as I expected.

On examining I found only a slight wound from an arrow on his hip bone, but he was not so much to blame as he was a young man who had been brought up in Missouri, the pet of the family and had never done or learned much of anything but horseracing and gambling whilst under the care of his parents (if care it can be called).

I pulled off an old piece of a coat made of blanket (as he was entirely without clothing except his hat and shirt)—set myself in a leaning position against a tree ever and anon gathering such leaves and rubbish as I could reach without altering the position of my body to keep up a little fire in this manner miserably spent the night.

It was now ninety miles to Fort Hall and we expected to see little or no game on the route, but we determined to travel it in three days. We lay down and shivered with the cold till daylight then arose and again pursued our journey towards the fork of Snake river where we arrived sun about an hour high forded the river which was nearly swimming and encamped. The weather being very cold and fording the river so late at night caused me much suffering during the night. September 4th we were on our way at daybreak and traveled all day through the high Sage and sand down Snake River. We stopped at dark nearly worn out with fatigue hunger and want of sleep as we had now traveled sixty-five in two days without eating. We sat and hovered over a small fire until another day appeared then set out as usual and traveled to within about 10 of the Fort when I was seized with a cramp in my wounded leg which compelled me to stop and sit down every thirty or forty rods. At length we discovered a half breed encamped in the valley who furnished us with horses and went with us to the fort where we arrived about sun an hour high being naked hungry wounded sleepy and fatigued. Here again I entered a trading post after being defeated by the Indians but the treatment was quite different from that which I had received at Laramie’s fork in 1837 when I had been defeated by the Crows.

The Fort was in charge of Mr. Courtney M. Walker who had been lately employed by the Hudsons Bay Company for that purpose He invited us into a room and ordered supper to be prepared immediately. Likewise such articles of clothing and Blankets as we called for.

After dressing ourselves and giving a brief history of our defeat and sufferings supper was brought in consisting of tea, cakes, buttermilk, dried meat, etc. I ate very sparingly as I had been three days fasting but drank so much strong tea that it kept me awake till after midnight. I continued to bathe my leg in warm salt water and applied a salve, which healed it in a very short time so that in ten days I was again setting traps for Beaver.

∞§∞

— Adapted from Journal of a Trapper [1834-1843] by Osborne Russell.

— Detail from a Library of Congress Image.

— You can read more by Osborn Russell in my book, Adventures in Yellowstone.

— You might also enjoy these tales by Mountain Men:

- “Hour Spring: A Geyser by Another Name” by Osborne Russell.

- “The First Written Description of Yellowstone Geysers” by Daniel T. Potts.

During the winter months when Yellowstone Park was buried under 20-foot snowdrifts, my sales rank bounced around between a hundred thousand and a million. I know that doesn’t sound impressive, but you should recall that there are about six million titles available on Amazon so that’s well within the top twenty percent.

During the winter months when Yellowstone Park was buried under 20-foot snowdrifts, my sales rank bounced around between a hundred thousand and a million. I know that doesn’t sound impressive, but you should recall that there are about six million titles available on Amazon so that’s well within the top twenty percent.

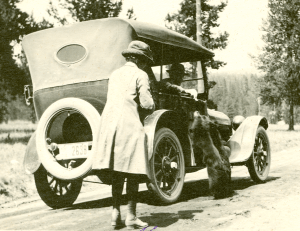

In 1915 when cars were officially allowed in the park, the action transformed the Yellowstone experience. As the story below shows, fears of auto-induced mayhem proved to be unfounded.

In 1915 when cars were officially allowed in the park, the action transformed the Yellowstone experience. As the story below shows, fears of auto-induced mayhem proved to be unfounded.